May 31, 2024

My grade eight music teacher was a short lady with dark, slightly graying hair, always tied back in a bun. She wore large glasses that turned shaded in the sun, and used the omnichord, an electronic instrument to teach us new songs. She sometimes invited students to play it in front of the class.

It was the spring of 1991 when she taught us, of all songs, Smells Like Teen Spirit, from the new grunge band Nirvana. I had heard of them, but had not really yet listened to their new album, Nevermind. I was only beginning to become interested in music, but I had caught the buzz regarding this charismatic, dynamic musical trio from the West Coast. They possessed a new sound that didn’t fit the rock music genre that my older cousin introduced me to, such as Def Leppard or Guns n’Roses. I thought these bands were cool because my cousin thought they were. But I didn’t really connect with them.

With Nirvana, on the other hand, something resonated. Nevermind contained wonderful, complicated, but open-minded anthems like Come As You Are, and challenging, vulgar songs like Territorial Pissings, which exposed our latent animal tendency for marking boundaries. Cobain sang in glorious contradictions, sarcasm, and irony. Overall, the music was just really good and really cool. And still is.

The idea of challenging our cultural boundaries through the kind of spirit that Nirvana embodied caught my imagination. It began to shape my moral and spiritual disposition. I would not solely credit Kurt Cobain and Nirvana for this, but perhaps their music and what they represented culturally poured gasoline on a fire that had already been kindled in me, as it did for many people around the world in the early 90s.

I was at a critical spiritual and moral juncture in my life. Would I learn from, and conform to, the moral values of my community, especially those of my parents and church community, which were fairly conservative in orientation? Or would I rebel against this expectation? I wanted to push the boundaries and affirm my own will, seeking to form a new identity.

I chose rebellion.

Gasping for Air

I recently read the book Come as You Are: the Story of Nirvana, by Michael Azerrad, which sheds much light on the art of Nirvana in its cultural context of the time. It reads as–and certainly is, especially in light the suicide of Kurt Cobain–a tragedy.

The reality is that my life was the polar opposite to his. I grew up in a stable home, while he did not. His parents divorced at a young age. Constantly passed around to different family members for most of his life, he never truly felt wanted or accepted. In the book, Kurt comments that his story of being raised in a broken home in the 1980’s was common, as “every parent made the same mistake . . . I don’t know exactly what it is, but my story is exactly the same as 90 percent of everyone my age” (Come As You Are, 221).

For Cobain, it was a story of the loss of innocence. The book comments that the image of the naked baby in the pool on the cover of Nevermind captures this, that “the image probably appealed to Kurt because it echoed his ideas about recapturing his innocent childhood bliss…” (Come As You Are, 183).

Indeed, the music of Nirvana expresses a kind of broken, twisted grasp for a childlike innocence that is being lost. Even drummer David Grohl confessed it felt like they were singing “children’s music,” for a confused generation (see Apple Music description of Nirvana). And perhaps the music, too, was a kind of rebirth of creative expression derived out of this brokenness. Cobain also experienced this reality of the world when confronted with the corporate music scene and media. The cover of Nevermind expresses this as well; the feeling of innocence being exploited by capitalism and the allure of fame. Cobain struggled to adjust to this reality and the pressures that went along with this.

Contesting for Freedom

Although I was raised in a stable home, I still decided to take the path of rebellion. It is absurd, really. It is a mystery. I was like Adam and Eve questioning the safety of the garden of Eden. My parents were hard-working, caring, and blessed me in every way conceivable. I know that I wanted social acceptance, to be held in respect and esteem among my peers. I was in search of a new community apart from the conservative, Christian one represented by my parents. In fact, I began to feel embarrassed for how different they were from people.

Teenage rebellion brought a new kind of identity and social community. Nirvana embodied this yearning for me. It was loud, abrasive, sarcastic and destructive. It was a spirit that refused to bend and bow to the bullies of the world. It was a will to defy the powers and principalities of the dominant culture. It was really a cry for a new kind of freedom, against a false promise of a new modern Eden in the Western world.

This was what “punk” represented: a confrontational challenge to the centers of power in society. The Punk movement of the late seventies and eighties, which influenced Nirvana, was really an idealist and aesthetic movement that rebelled against the perceived evils of the corporate and capitalist world (Come As You Are, 213). It was a desire to be authentic, to value one’s friends and community, to party and have a good time on our own terms. It was a protest for freedom from all constraints, a freedom to be who we wanted to be.

It was the freedom to self-medicate in light of the harsh realities of the world. Freedom to have sex on one’s own terms, regardless of traditional cultural expectations. For many, it was the freedom to escape from the destructive behaviors and habits of their broken home life into the comfort of their friendship circle. For me, this freedom was the thrill of transgression, and breaking the social norms became a kind of drug in itself.

A Confrontation with Tragedy

This “thrill of freedom” began to crash in 1994 when Kurt Cobain committed suicide. This really disturbed me. I remember seeing it on the news at home. I walked out into our yard, wandering aimlessly, wondering what it meant. Why would he kill himself? Why would he shoot himself in the face?

I will not speculate on Cobain’s motives and what brought him to this final and terrible act. It is still a mystery. However, the event did impact me and caused me to question the notion of “freedom” that I was trying to live and embody.

The term “nirvana,” derived from Buddhism, is literally defined as the extinguishment of desire, for the desire is seen as the source of all suffering. Is suicide the final and ultimate act of freedom to escape the pain, suffering, and brokeness of life and the world? Is it an expression of the freedom to die on one’s own terms, to extinguish desire and feeling forever?

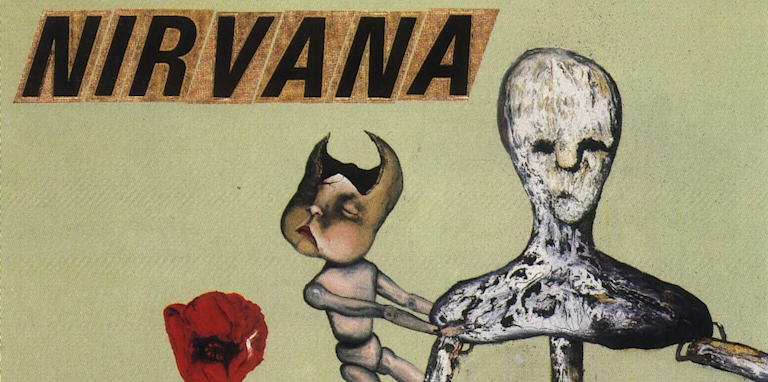

The cover of In Utero is an image of a damaged baby clinging to a “skeletal parental future which seems to be ignoring the baby,” while it looks longingly at poppies (Come As You Are, 295). Azzerad cannot help but comment on the autobiographical implication. Quoting Dylan Carlson, a friend of Kurt’s, he interprets his art as, “innocence and authentic vision beset upon a cruel and uncaring universe. Artists continually attempt to extract beauty from the world and are unable to because of being denied the beautific relationship with the world” (Come As You Are, 295).

In confronting the reality of death, Cobain became more than a cultural icon for me; he became a kind of (anti)spiritual and moral guide, though it was never his intention to become one. He would have mocked the very idea. For me personally, his suicide sent a strong message: Don’t follow me, you idiot. The story of Nirvana represents my own personal desire for a new authentic freedom, the creation of a new innocence. One could argue, it represented my desire to create a new kind of personal identity. But it also meant the despair of skepticism, that this freedom may be impossible to truly acquire, still standing outside of Eden.

Read Part 2: Questioning Divine Necessity

Go to the series: Transfiguration in Time

Sources

Azerrad, Michael. Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana. New York: Broadway Books, 1993.