May 31, 2024

I discovered the band Heilung (healing) in my first year in Germany. They wear deer antlers and play with real animal bones. They use ancient Germanic script for their lyrics. People who attend their concerts describe it as an overwhelming spiritual experience that taps into something primal within them. Even on Youtube, one can be transported into a new world musically and visually.

Although Heilung has metal roots, they are more than this. They describe their music as “amplified history,” an effort to recapture or reimagine a spirituality connected with nature that predates Christianity and Christendom in Europe. If Kurt Cobain represents a raw expression of the loss of innocence, Heilung attempts to reimagine it.

Are they trying to recapture a loss of “innocence,” an indigenous spiritual connection to nature? Or are they proposing something new? Certainly their name speaks to their intent: healing. What does it mean to heal from the stain of Christianity on European soil? Their intention is to provide an alternative to Christianity, a modern neopagan attempt to return to the garden, but intune with all our primal human desires.

The Void of Meaning

The art of Heilung reminds me of another kind of anti-spiritual guide, the German poet and philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche was a philology professor in Basel in the 19th century, until health issues led him to an early retirement, where he focused solely on his philosophical work.

I was introduced to his writing as an undergraduate student. What impressed me about Nietzsche was, not only content, but his style and the spirit in which he wrote. He wrote with a deep passion and has had a profound influence on people in Western culture and beyond.

Like Cobain, he is often misunderstood. He, too, wrote in riddles and contradictions. In a famous text, he wrote about a “mad man,” running around a marketplace causing a disturbance and screaming, “I seek God! I seek God!” The problem is that the man realizes that God is dead. In fact, God does not just die of natural causes, but was deliberately murdered, “‘Whither is God?’ he cried; ‘I will tell you. We have killed him–you and I’” (The Gay Science, 181)

The people in the marketplace laugh at him. More than a century later, Trent Rezner of Nine Inch Nails wrote a song with the chorus, “God is dead and no one cares.” Who cares if we have murdered God or not? Does it matter if there is a God or not?

Nietzsche seemed to understand the implications of this “act.” The madman’s concern is not just about God being dead, but about what is left in the void, “How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? . . . What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent?” (The Gay Science, 181)

What happens when we have eliminated the force that gave meaning, purpose, and moral direction to our lives? What happens when we cut off the metaphysical branch on which we are sitting? What happens when the anchor is cut and we are left adrift in a sea of moral and philosophical chaos?

A short reflection such as this does not afford a serious, sustained response to these questions. But on a personal level, I can resonate with this. In my own heart, as I drifted from faith in God, violent and chaotic impulses were unleashed in me that were difficult to control. I will explore this underlying "will to power" further in Part 3 and 4.

However, Nietzsche's text reminds me of a time when my cousin and brother and I ventured off into a forest as young boys. We climbed up three evergreen trees and began to sway back and forth. As we did this, my brother's branch actually snapped. He was still clinging to it as he fell down through the branches until I could no longer see him. Thankfully, we were on a hill and the ground was covered in a soft layer of needles. He had no physical injuries. But it serves as an image for something that seemed to "snap" in me, breaking off from the metaphysical branch of faith, on which I was perched as a child.

Questioning my Inheritance

Despite the “death of God” in our Western societies, I was born into a family where the Christian faith was the most important aspect of life. Apparently, my family had not yet heard the madman’s news in the marketplace.

I was raised in an evangelical, Mennonite family. My grandparents fled the Russian revolution in the mid 1920s to settle and begin a new life in Canada. They were people of faith. My parents prayed to God, read the Bible daily, and were active in a local church. Naturally, I was taught to do these things as well. However, for my parents, these were not just religious rituals and practices, but they actually believed God existed and was present in our lives. When they prayed, they had faith that God heard them and guided them and provided for them.

However, I began to question this way of life and these values. Like the prodigal son in the parable of Jesus, I rejected my "father" and demanded my independence. According to New Testament scholar Kenneth Bailey, the son’s demand for his inheritance was actually a wish for the death of his father. I cannot help but see myself in this story. Did I actually wish for the death of God in my life? As I wrote in Part 1, I just wanted to live life on my own terms, the way that I wanted. To be more honest, what I sought was the acceptance of my friends, masked with the desire for self-determination.

In reality, I was being influenced by social and cultural forces that were much larger than me. It is widely known that in Western societies there have been strong cultural winds endeavouring to question God's place in society. Even Nirvana's song, Lithium, is an update on Marx’s description of religion as the “opiate of the masses” (Come As You Are, 218). There has been a powerful attempt to replace God with a general faith in humanity itself. In Eastern Europe, this faith was expressed through communism. In the West, it has been through a faith in individual freedom.

The Christian heritage bequeathed to Western nations transformed into a new humanism. Nietzsche, however, saw that “humanity” was no substitute for God.

No Longer Persuaded

What did “God '' mean, for premodern Western societies, and precisely how “Christian” was this conception? Certainly, there were serious disciples and followers of Jesus in the medieval period. I still find reading the works of Augustine and later authors theologically and spiritually rewarding. There was certainly a general belief in God in medieval Europe, however this was understood.

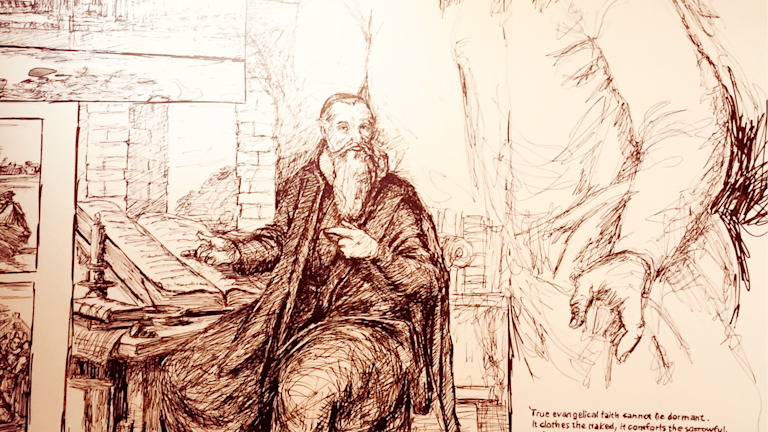

The Mennonite tradition, which has shaped me, stems from an early Anabaptism movement, that was relegated to the fringes of European society. It provided alternative interpretations of Scripture, differing from those of the dominant Roman Catholic church (see Valerie Rempel's The Birth of Anabaptism). In the 16th century, people like Menno Simons attempted to unify this fringe movement and provide a solid biblical foundation and ecclesial structure.

However, during the next centuries, much blood would be spilled over the politics of the Christian religion, exhausting people in their belief in God.

“God is dead” meant the decline of faith in the God of Christianity in our Western societies. This is what Nietzsche’s madman perceives and proclaims; religion may play a role in some people’s lives, perhaps in a private way, but the medieval dream of a unified, catholic society, where the church is the central moral and spiritual authority in the culture and state is, at least in many Western societies, dead.

I now live in Germany, where there are old churches in the center of every city and town, still echoing a cultural past where God was seen as being above civic life. I often hear church bells near the cafe where I sometimes work. There is a memory of God, but it is just that: a distant echo of a religious and cultural life that no longer exists. The majority of people have moved on from this old quaint belief in what a friend of mine described as an “imaginary best friend.”

In this void, bands such as Heilung emerge, seeking to revision a postchristian West, spiritual, but rooted in the soil, in nature.

The reasons for the decline of faith in God are complex. The rise of science and the expansion of our knowledge of the physical and psychological world? A new materialist mentality? The exhaustion of religiously motivated violence? The people of the ancient and medieval periods lived with the constant threat of sickness and death, the promise of an eternal afterlife was profoundly attractive. Have we lost the urgency of the need for God? Is “God” no longer “necessary?”

No Need to Pray

I remember one moment as an adolescent, twelve-years-old or so, when my parents left me home alone for the first time. When they did not return when I thought they would, I thought that what the Bible called “rapture” had occurred, and I was left behind. At that moment, I remember sincerely praying. But then, when I saw their car roll into the driveway, the existential dread left. It no longer seemed necessary to pray.

It is strange to remember what I thought of God during the time of my teenage rebellion. The truth is, I didn’t really think of him much at all. I was too obsessed with my new vision of freedom and the pursuit of my own happiness. The idea of God was familiar to me, since I was born and raised in a religious home, but God also did not seem real to me in a personal way.

Perhaps it was because, materialistically, I had it so good.

I live in a post-industrial, technological, capitalist society which has accumulated tremendous wealth and has extended human life. I have not experienced poverty like so many people in the world do. In fact, I was sheltered and ignorant of much of the experience of people that lived outside of my little comfortable Canadian town. There were certainly people who did not have as much to live on in my town, but they were not starving to death.

While I did not grow up in wealth and luxury, we had everything we needed, and more. I would not conclude that it was this material comfort that led me to unbelief in God. Nonetheless, when not faced with the constant risk of suffering and death, how could that not influence me to take for granted what I had?

Read Part 3: A War of (Compatible) Natures

Go to the series: A Transfiguration in Time

Sources

Azerrad, Michael. Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana. New York: Broadway Books, 1993.

Bender, Harold S. The Anabaptist Vision. @ thedockforlearning.org

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Random House, 1974.

See also nietzschesource.org

Suderman, Alex D. The Sacrament of Desire: The Poetics of Fyodor Dostoevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche in Critical Dialogue with Henri de Lubac. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2022.